![]()

| David Bowie 1947/2016 |

|

![]()

How the singer, style icon, and eternal chameleon ch-ch-changed pop culture forever.

By Kyle Anderson in Entertainment Weekly

![]() 'm not a nostalgic person," David Bowie said in 1997 on the occasion of his 50th birthday, a milestone he celebrated with a concert at New York City's Madison Square Garden. The rock icon was discussing his decision to perform that night with younger artists, including Foo Fighters and Smashing Pumpkins' Billy Corgan, instead of with contemporaries and longtime friends such as the Rolling Stones or Tina Turner. But with those five succinct words, he might as well have been summing up his entire approach to his career -- one that yielded 28 studio albums, will over 100 million records sold worldwide, and an influence that has spanned generations and disciplines, inspiring everyone from Madonna and Annie Lennox to Arcade Fire, Kayne West, and Lorde. "My reason for performing is not to please an audience," Bowie continued. "It's to present what I believe are exciting new ideas."

'm not a nostalgic person," David Bowie said in 1997 on the occasion of his 50th birthday, a milestone he celebrated with a concert at New York City's Madison Square Garden. The rock icon was discussing his decision to perform that night with younger artists, including Foo Fighters and Smashing Pumpkins' Billy Corgan, instead of with contemporaries and longtime friends such as the Rolling Stones or Tina Turner. But with those five succinct words, he might as well have been summing up his entire approach to his career -- one that yielded 28 studio albums, will over 100 million records sold worldwide, and an influence that has spanned generations and disciplines, inspiring everyone from Madonna and Annie Lennox to Arcade Fire, Kayne West, and Lorde. "My reason for performing is not to please an audience," Bowie continued. "It's to present what I believe are exciting new ideas."

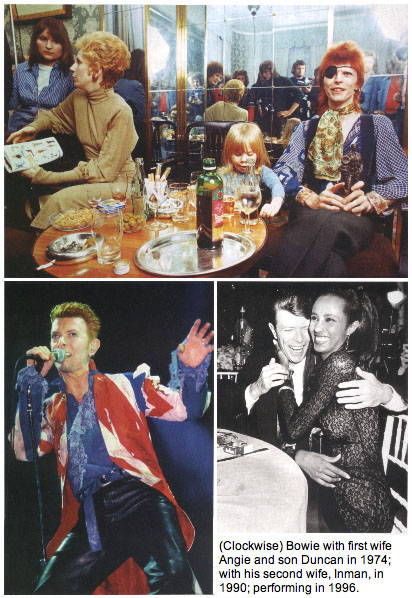

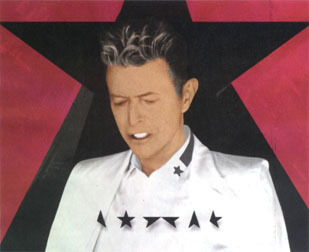

For more than 40 years, he was rock & roll's greatest innovator, blazing a trail right up until the end. His acclaimed final album, Blackstar, was released on his 69th birthday, just two days before his Jan. 10 passing. Following a very private 18-month struggle with cancer, the artists "died peacefully," according to a public statement, and "surrounded by his family," which included two children, daughter Alexandria, 15, and son Duncan, 44, and his devoted second wife, supermodel Iman, 60, whom he married in 1992. Even those closest to the musician were shocked by news of his death. "I received an email from him seven days ago," said Brian Eno, who collaborated with Bowie on classic albums like 1977's Low and "Heroes," in a statement. "It was funny as always, and as surreal, looping through word games and allusions and all the usual stuff we did. It ended with this sentence: "Thank you for our good times, brian. they will never rot." And it was signed 'Dawn.' I realize now he was saying goodbye."

Just one month earlier, on Dec. 7, Bowie made his final public appearance at the premiere of his Off Broadway musical Lazarus in New York City. "He seemed truly at peace and excited by what he was experiencing," said James Nicola, artistic director of New York Theatre Workshop, which is presenting the production. "He floated into the lobby, really happy."

Like the planet-hopping astral beings he conjured on the 1972 album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars and in the 1976 film The Man Who Fell to Earth, Bowie was constantly stepping into the unknown, reinventing himself with astonishing regularity and innovating at the drop of a bespoke hat. He morphed and moved on and never looked back, leaving the past where he thought it belonged. "My strength has always been that I never gave a s--- about what people thought of what I was doing," he told Q magazine in 1989. "I'd be prepared to completely change from album to album and ostracize everybody that may have been pulled in to the last album. That didn't even bother me one iota."

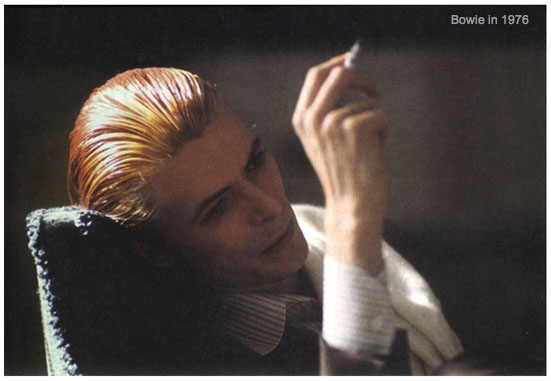

But even a brilliant extraterrestrial like Bowie had to start out as a mere mortal. Before he revolutionized rock & roll with androgynous characters like Ziggy Stardust, he was born David Robert Jones to working-class parents in 1947 London. As a child, he was already looking beyond Britain's borders: He was tuned into American pop and jazz pioneers like Little Richard and John Coltrane. "I had America mania when I was a kid, but I loved all the things that America rejects," he told Entertainment Weekly in 1997. "It was black music, it was the beatnik poets, it was all the stuff that I thought was the true rebellious subversive side." His earliest recordings were released under the name Davie (or sometimes Davy) Jones, but, unhappy about his lack of success with that moniker -- and to avoid confusion with the Monkees singer of the same name -- he rechristened himself David Bowie. "I have no confidence in David Jones as a public figure," Bowie told People in 1976. The new name -- inspired by what he said was "the ultimate American knife" -- was "the medium for a conglomerate of statements and illusions."

But even a brilliant extraterrestrial like Bowie had to start out as a mere mortal. Before he revolutionized rock & roll with androgynous characters like Ziggy Stardust, he was born David Robert Jones to working-class parents in 1947 London. As a child, he was already looking beyond Britain's borders: He was tuned into American pop and jazz pioneers like Little Richard and John Coltrane. "I had America mania when I was a kid, but I loved all the things that America rejects," he told Entertainment Weekly in 1997. "It was black music, it was the beatnik poets, it was all the stuff that I thought was the true rebellious subversive side." His earliest recordings were released under the name Davie (or sometimes Davy) Jones, but, unhappy about his lack of success with that moniker -- and to avoid confusion with the Monkees singer of the same name -- he rechristened himself David Bowie. "I have no confidence in David Jones as a public figure," Bowie told People in 1976. The new name -- inspired by what he said was "the ultimate American knife" -- was "the medium for a conglomerate of statements and illusions."

It wouldn't be Bowie's last reinvention, of course. After early singles failed to catch on, he scored his first notice with the 1969 single "Space Oddity," its rise coinciding with the return of the Apollo 11 astronauts in July. A chart hit in the U.K., the track was considered a novelty in the States, but it helped set Bowie on a lifelong journey of mutation and innovation. "I'm very aware of the impact I've had in Europe," Bowie said. "But my impression of the reception of the reception I'd had in America was 'Oh, here comes this eccentric limey again,' I never felt that I'd contributed much to the fabric of American rock."

That all changed in 1972 when Bowie dreamed up an intergalactic alter ego named Ziggy Stardust, whom he introduced on the album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars. One of the first -- and most important -- concept albums in rock & roll, Ziggy told the tale of an Earth on the brink of Armageddon and the interstellar rock god sent to save it. The album also paved the way for future generations of androgynous, gender-bending icons in pop. "He was emaciated, he had bright orange hair and silver lipstick and no eyebrows, and he looked fantastic," the Cure's Robert Smith told Entertainment Weekly in 1997. "The potency of the image was so strong that the next day at school everyone was saying, 'Did you see Bowie on Top of the Pops?'"

It's trite to point out, but no less true: Nobody had seen (or heard) anything like him in pop music before. Here was a guy performing with cabaret-glam theatricality in women's clothing -- but he was playing loud, tough, hummable rock songs. It started Bowie on the road to being a barrier-busting hero who acted as an avatar for gender fluidity before that was even a term. (He stayed loyal to the cause: In 2014 he appeared in a PSA with Tilda Swinton that declared "Gender is between your ears, not between your legs.") But the fundamental power of the tunes on Ziggy Stardust could not be denied, and the album helped launch Bowie into the orbit of stars such as Mick Jagger. "David was always an inspiration to me and a true original," Jagger said in a statement. "He was wonderfully shameless in his work, we had so many good times together."

But Bowie's struggles with drugs, specifically cocaine, took their toll in the 1970s. Station to Station may be regarded as one of his most vital releases, but he noted that his penchant for partying was so intense during the era that he recalls little about the actual creation of the album. "I was flying out there, really in a bad way," he told Q in 1997. "I listen to Station to Station as a piece of work by an entirely different person."

In an effort to get clean, Bowie relocated to Switzerland in 1976 and eventually settled in Germany. There he teamed with Brian Eno to craft what became known as his Berlin Trilogy of albums -- 1977's Low and "Heroes," and 1979's Lodger -- which set his dystopian obsessions against the still-emerging electronic sounds that would inform the radio-friendly new wave of the '80s. "In the mid-to late '70s Berlin was an incredible city," his friend and collaborator Giorgio Moroder says. "There were a lot of things happening, the the nightclubs were open 25 hours. It was a great experience in Berlin for him."

Mass audiences finally caught up with Bowie at the dawn of the MTV era. He had been crafting music videos long before there was a proper outlet for them, but the cable channel gave him a platform for clips like 1983's "China Girl," which helped turn him into an international pop sensation. Even as MTV boosted him, though, he was never afraid to bite the hand that fed him. "It occurred to me, having watched MTV over the last few months, that it's a solid enterprise, really. It's got a lot going for it. I'm just floored by the fact that there are so few black artists featured on it," he told VJ Mark Goodman during an on-air interview in 1983. "Why is that?"

Bowie's creative impulses never wavered either, whether he was teaming up with Nile Rodgers for the hit album Let's Dance or pursuing film roles like his memorable turn as Jareth the Goblin King in 1986's Labrynth. "I've always called him the Picasso of rock & roll," Rodgers says. "We were doing Let's Dance and one day he came to my apartment and he was sort of hiding something behind his back. And he says, 'Nile, darling, I want the album to sound like this.' And he whipped out a picture of Little Richard in a red suit getting into a red Cadillac convertible. I new exactly what he was talking about."

Bowie's creative impulses never wavered either, whether he was teaming up with Nile Rodgers for the hit album Let's Dance or pursuing film roles like his memorable turn as Jareth the Goblin King in 1986's Labrynth. "I've always called him the Picasso of rock & roll," Rodgers says. "We were doing Let's Dance and one day he came to my apartment and he was sort of hiding something behind his back. And he says, 'Nile, darling, I want the album to sound like this.' And he whipped out a picture of Little Richard in a red suit getting into a red Cadillac convertible. I new exactly what he was talking about."

As grunge and alternative revolutionized music in the 1990s, Bowie was there too, as an artist who was part of the conversation and as a godhead to a new generation of musicians. Some of them became collaborators and friends. Trent Reznor cited Bowie as a major influence, and in 1995 his band Nine Inch Nails toured with Bowie. "That's one of those things where I still look back and go, 'Oh man, that actually really happened,'" Reznor told Entertainment Weekly in 2014. "He came to me and said, 'I made this difficult album [1995's Outside] with Eno, and we're probably going to bum everybody out because we're just going to play stuff off this record. We're not going to do any hits, because that's what I want to do.' I thought that took real courage and conviction.... He's the real deal. He's one of those few people who didn't disappoint you when you actually get to know them."

As Bowie advanced into his 50s, his creative output began to wane. Following the release of 2003's Reality he had planned a massive world tour, but the trek had to be cut short when a blocked artery required surgery, and he performed his last full concert in Germany on June 25, 2004. (His final performance would be a "Changes" duet with Alicia Keys in New York City in 2006.) Still, he continued to be a champion of new sounds -- he could often be seen scoping out indie-rock bands in New York's downtown clubs -- and collaborated with such acts as Arcade Fire and TV on the Radio. "Every report I'd heard about 'meeting Bowie' suggests that the guy was really, really good at meeting people and making them feel like a million bucks," recalled Arcade Fire's Owen Pallett, who recorded with Bowie on the title track to the band's 2013 album Reflektor. "But no words could really describe the man's complete generosity of spirit, intelligence and charisma."

One possible reason for Bowie's retreat from the spotlight at this time: rampant speculation that his health was in decline. While Bowie never spoke about it to the press, his longtime musical partner Tony Visconti told The Hollywood Reporter in 2013, "We all know he had a health scare. I hate to hear it described as a major heart attack -- it was not a major heart attack -- but he had surgery in 2004 and he's been healthy ever since." Sara Gibbons, who appears in the video for "Blackstar," tells of an encounter with Bowie in upstate New York a few years later: "He had told me about the heart attack he had -- but he seemed terrific." Despite Bowie's hiatus from recording, he kept busy, guesting on the Ricky Gervais series Extras and curating the inaugural High Line Festival in New York.

Then came 2013 -- and a triumphant return with his 27th studio album, The Next Day, a startlingly vibrant collection that bridged the past and future of Bowie's musical career. That creative spark continued through his final album, Blackstar. According to Visconti, the record was intentionally crafted as his farewell. "He really wanted to do something new and to push the boundaries," saxophone player Donny McCaslin says about recording with Bowie on Blackstar. "I didn't notice him reaching back. I just felt like he's pushing."

All his life, Bowie never stopped his restless reach toward the unknown. "There's a song on his album Low called 'Speed of Life,' and that the speed at which he seemed to move -- his music and his image and his focus were always changing, and always in motion," said Martin Scorsese, who directed Bowie in 1988's The Last Temptation of Christ. "With every movement, every change, he left a deep imprint on culture." ![]()

| The Starman Signs Off |

|

![]()

Inside the making of 'Blackstar', Bowie's farewell album.

by Eric Renner Brown in Entertainment Weekly

![]() hen David Bowie entered a New York City studio in January 2015 to record his 28th (and final) studio album, Blackstar, he had already been battling cancer for about six months. But the restless journeyman was determined to continue experimenting despite his illness. For these seven songs, the rocker tapped progressive jazz saxophonist Donny McCaslin and his tight-knit group of collaborators to bring demos like "Lazarus" and "Dollar Days" to life.

hen David Bowie entered a New York City studio in January 2015 to record his 28th (and final) studio album, Blackstar, he had already been battling cancer for about six months. But the restless journeyman was determined to continue experimenting despite his illness. For these seven songs, the rocker tapped progressive jazz saxophonist Donny McCaslin and his tight-knit group of collaborators to bring demos like "Lazarus" and "Dollar Days" to life.

"He was singing very passionately with a lot of energy and a lot of conviction, and we were inspired by that," McCaslin said of the sessions, which spanned three one-week chunks from January to March at the Magic Shop studio in SoHo, a few blocks from Bowie's home. "He said something to me like 'Donny, I don't know what's going to come of this, but let's have some fun.' The spirit couldn't have been better."

"He was singing very passionately with a lot of energy and a lot of conviction, and we were inspired by that," McCaslin said of the sessions, which spanned three one-week chunks from January to March at the Magic Shop studio in SoHo, a few blocks from Bowie's home. "He said something to me like 'Donny, I don't know what's going to come of this, but let's have some fun.' The spirit couldn't have been better."

Now, after his death, fans are listening to these lyrics knowing that Bowie was well aware of his end -- especially the haunting title track ("Something happened on the day he died/ Spirit rose a metre and stepped aside") and the album's heartbreaking coda "I Can't Give Everything Away," one of the finest songs he ever wrote. Despite the record's dark lyrical content, humor and spontaneity dominated the sessions, which would run from 11 a.m. until 4 p.m. Bowie took an active role in the process, performing tracks in the room with the band and encouraging communication, interplay, and risk taking. "He was so present in the moment and so focused on pushing the envelope," McCaslin recalls. "It's progressive, boundary-pushing music."

Bowie also drew influences beyond his close crew of producer Tony Visconti and McCaslin's ensemble. LCD Soundsystem's James Murphy stopped by multiple times in February to add "neat percussion sounds," McCaslin says. And Bowie "was reading all the time" and digesting plenty of new music. He raved about D'Angelo's Black Messiah, which dropped shortly before the sessions began, as well as Kendrick Lamar's To Pimp a Butterfly, which came out near the conclusion.

After a day's worth of final overdubs with McCaslin last spring, Bowie and Visconti sequestered themselves to assemble the recordings into a cohesive album. But McCaslin met with Bowie once more in November to hear the result. "It was overwhelming to me just to hear the whole sonic montage and how they kind of put it all together," McCaslin says. "I think he was very happy with how the record turned out." ![]()

![]() Reader's Comments

Reader's Comments

No comments so far, be the first to comment.