![]()

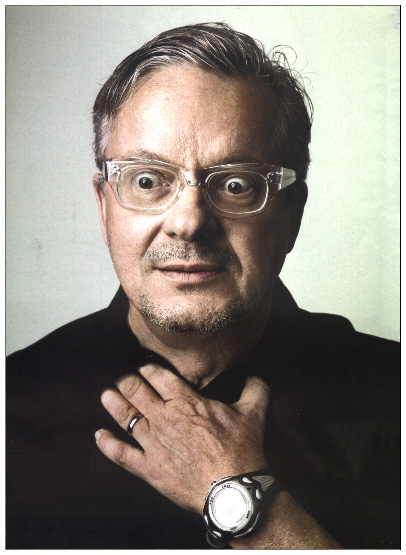

| What I've Learned by Mark Mothersbaugh |

|

![]()

The 63-year-old musician and Devo co-founder, whose scoring credits include several

Wes Anderson films as well as the hot new 'The Lego Movie', is interviewed on 12/4/13.

Interviewed by Cal Fussman in Esquire

![]() e were looking for a name for the band. We're going, "Well, there's Art Deco, Art Nouveau...we're Art De-veau." We just kept shortening it until we had Devo. And everybody went, "That's it!"

e were looking for a name for the band. We're going, "Well, there's Art Deco, Art Nouveau...we're Art De-veau." We just kept shortening it until we had Devo. And everybody went, "That's it!"

Devo could have been a church that married creationism and evolution. Science and faith could have come together and held hands as Devolution and we could have changed everything. Instead of going to clubs and dancing disco, we could have had a church that would have done organized calisthenics.

I always thought of disco as a beautiful woman with no brain.

In the mid-seventies, I saw a Burger King commercial on TV. They had taken Pachelbel's "Canon," which was a beautiful piece of classical music, and turned it into: Hold the pickle/hold the lettuce/special orders don't upset us./All we ask is that you let us serve it your way. And I was like, Oh my God! They know how to change how people think! They know how to make people do things! They don't use rebellion. They use subversion! I thought, It's so evil, yet it's perfect!

I think my dad would have been an artist if he'd had the choice.

Some girl in elementary school asked my, "Why do you have a head like a lightbulb?" And I'm like, Oh, f---! I do, don't I?

The teacher would say: "Read what it says on the board," and I'd go, "What's a board?" Then everybody would laugh and the things to say when they ask you a question like that? I knew people had some information I didn't have. One day someone saw me doing homework and told my parents, "Maybe you should get his eyes tested." I remember coming out of the optometrist with glasses and going over a hill and seeing rooftops, smoke coming out of chimneys, the tops of trees, clouds! I started drawing and painting. I've been an artist since that day.

I probably wouldn't enjoy a potato-chip sandwich on white bread with mustard now. But at the time...

My brother and I talked about which toe to shoot off so you wouldn't have to go to Vietnam. We were thinking the little toe, because that's so little. Then I read that if you lose your little toe, you can go something like six months without being able to walk because you lose your equilibrium. So I thought, Maybe it's gotta be the middle toe? Then I got this letter that said: How would you like to go to college for a cut rate? I'm in. Kent State.

I was a few blocks away from the shootings when it happened. They shut down the school in May, so we couldn't finish '70s. We were playing in bands, and I started searching for the sounds of V-2 rockets and mortar blasts and ray guns -- things that related to our culture, to what was happening on the news and in our world. I was looking for sounds that nobody was using in music.

After the shootings, we thought we were gonna bo back to school and it would be electrifying. Instead, it was like all of a sudden everybody had turned conformist. The whole thing had gotten too real for people, and so it was just like they all went to sleep.

Forty years ago, I would have been an asshole for a husband.

Even at fifty, I though marriage was an absurd concept. I needed to get wiser to get married.

I married a woman who I thought didn't have a strong opinion about kids. I never wanted to have kids. It's partly because I grew up with two sisters and two brothers in a three-bedroom house and I had to share a bed with two brothers. One would kick or scratch the other to get a bloody nose and we'd all be angry. But for my wife, children became more and more important. A year or two into our marriage, she was like, "I know you don't want to have kids because the planet's overpopulated, but how about if we adopt?" Okay, yeah...I wasn't paying attention. I was working with Wes on something when she said, "Mark, we're going to China in three months to pick up our baby." And I'm like, Really?

There's eight couples, we go into this industrial building, get into this freight elevator with a hideous neon light that's making everybody kind of greenish and flickering on and off as we go up slowly -- right out of a David Lynch movie. It takes forever, but then the doors open and there are eight nannies, each with a baby. And I go: That's my baby.

My feeling is that Wes Anderson has not done his best work yet.

A friend named Paul Reubens had a TV show called Pee-wee's Playhouse. He called me up and asked, "Will you score my show? Here's our direction: When it's sad, make it really sad. When it's happy, make it really happy. When it's crazy, make it really crazy." After the show was a hit, I got calls from everybody to score their shows. I told them, "If you want to save $5,000 on music for your TV show, make the contract three or four pages long, so I can read it. If it's too long and I can't read it, then I have to hire a lawyer and you can just add another $5,000 to the cost." ![]()

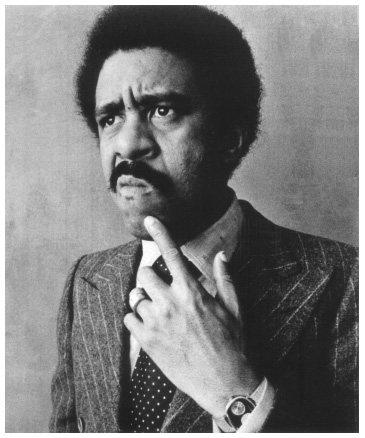

| How To Make a Richard Pryor |

|

![]()

He was labeled a genius, a racist, a pioneer, a junkie, a

lunatic. A new biography looks at him simply as a man.

by Tom Chiarella in Esquire

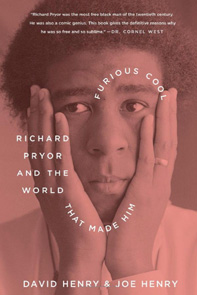

![]() ou just say Richard Pryor. You don't say stand-up comedian Richard Pryor. Or the late Richard Pryor. Just Richard Pryor. Hasn't worked in 20 years, been dead for 10, and he's still that big. So this is a review of Furious Cool: Richard Pryor and the World that Made Him (Algonquin, $18.90), a biography of Richard Pryor by brothers David and Joe Henry, who set out to make a biopic but ended up writing an addictively readable study of the path of this outsize-talent who traveled the wide way through recent American history. Richard Pryor. You still know him. And you never really did.

ou just say Richard Pryor. You don't say stand-up comedian Richard Pryor. Or the late Richard Pryor. Just Richard Pryor. Hasn't worked in 20 years, been dead for 10, and he's still that big. So this is a review of Furious Cool: Richard Pryor and the World that Made Him (Algonquin, $18.90), a biography of Richard Pryor by brothers David and Joe Henry, who set out to make a biopic but ended up writing an addictively readable study of the path of this outsize-talent who traveled the wide way through recent American history. Richard Pryor. You still know him. And you never really did.

There were always two essential truths about Richard Pryor, depending on whom you listened to, even (no, especially) the man himself: He didn't take any shit or he got shit on constantly. His act always rode the slippery balance between those two truths, as did the progress of his life, from his childhood in a Peoria, Illinois, whorehouse to his self-immolation whilst freebasing, from strip-club janitor to lounge act in the '50s to stand-up sensation of the '70s to star of movies (Stir Crazy; See No Evil, Hear No Evil; Brewster's Millions) that really earned in the '80s -- Richard Pryor, strong, black, brave, a pioneer. Or Richard Pryor: a skinny-armed, light-skinned, wife-beating egotist. All that, of course. Far more. The book tells the world as much, tracing the decades-long evolution of his stand-up act, the chaotic pattern of his success, the public spectacle of his fall. Richard Pryor did the same, of course, fearlessly showing his ass to the world. (Once, for a short-lived NBC show, he assured the audience the straitlaced network hadn't cut off his balls, even as the camera panned back to reveal that the makeup department had made his genitals disappear. The spot was pulled from the show.)

There were always two essential truths about Richard Pryor, depending on whom you listened to, even (no, especially) the man himself: He didn't take any shit or he got shit on constantly. His act always rode the slippery balance between those two truths, as did the progress of his life, from his childhood in a Peoria, Illinois, whorehouse to his self-immolation whilst freebasing, from strip-club janitor to lounge act in the '50s to stand-up sensation of the '70s to star of movies (Stir Crazy; See No Evil, Hear No Evil; Brewster's Millions) that really earned in the '80s -- Richard Pryor, strong, black, brave, a pioneer. Or Richard Pryor: a skinny-armed, light-skinned, wife-beating egotist. All that, of course. Far more. The book tells the world as much, tracing the decades-long evolution of his stand-up act, the chaotic pattern of his success, the public spectacle of his fall. Richard Pryor did the same, of course, fearlessly showing his ass to the world. (Once, for a short-lived NBC show, he assured the audience the straitlaced network hadn't cut off his balls, even as the camera panned back to reveal that the makeup department had made his genitals disappear. The spot was pulled from the show.)

Furious Cool is both a steady progression -- and an unflinching gaze, fixed upon the sometimes herky-jerky progress of Richard Pryor's routine and the flyaway personal life that fueled it. Its focus is most acute in the '70s, when Richard Pryor introduced the white world to the occasion of a black man using the word nigger onstage and off. The book makes a turn from blazing entertainment history to authoritative meditation on culture when the man steps onstage one night in Berkeley in 1971 and "just flat-out said it, like a man committing himself to a 12-step program:

"'Hello my name is Richard Pryor. I'm a nigger.'

"He said it again.

"'A nigger.'

Again and again. Just that one word, over and over..."

It's hard to imagine -- or remember, I guess -- a time when black comedians didn't, couldn't, access this word freely. Paul Mooney, Richard Pryor's longtime friend and writer, writes, "What we both like about the word is that it demonstrates a simple truth.... We are saying something that white people can't."

When you turn the last page of Furious Cool, you might be unsure what exactly happened to make the last part of the 20th century feel so compactly represented by, not to mention tangled up in, the life of Richard Pryor. Surely no one could be that much at or near the epicenter of 25 years of American life, always with the people who were it -- Tom Jones, Flip Wilson, Carson -- and in the places where it was at -- Greenwich Village, then Vegas, then Berkeley, then Hollywood. But the case is beautifully made in unpretentious and inventive prose, a veering tapestry of anecdotes that occasionally careens into dreamlike, charged passages jostling point of view. ("He emerges from a side window as though shot from a cannon: exploding free and trailing smoke," the book begins.) What's furious about Furious Cool is the energy and pain of the authors' discovery, the disquieting effect of a public life revisited and a dire compassion for the subject. Yes, sometimes the Henrys got too close. But they admit it. And they don't apologize. Instead, they continually advance into the torrent that was Richard Pryor's life.

Someday, when fewer people know Richard Pryor's name, Furious Cool will be the best defense against the worst sort of forgetting -- the kind that involves who we are now, who we loved once, and why.

I just want to type it again: Richard Pryor. ![]()

![]() Reader's Comments

Reader's Comments

No comments so far, be the first to comment.