![]()

| Diamond Life |

|

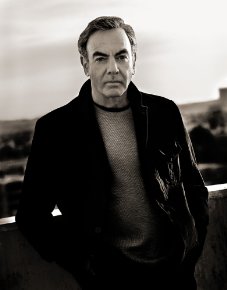

Thanks to Rick Rubin, 12 Songs returns Neil Diamond to his 'Solitary Man' greatness.

by Vanessa Grigoriadis in Rolling Stone

![]() his past summer, Neil Diamond ran into Mick Jagger at the Los Angeles studios where they were both working on new albums. "He came by to see what the hubbub was about, and we kidded around," says Diamond, a tan, happy man who looks a decade younger than his sixty-four years but speaks in the slow Brooklynese of a real old-timer. "I told him, 'You business office made a big faux pas, because they booked yuh tour the same month I'm going out.' I don't think he liked that." Diamond titters. "I thought it was funny."

his past summer, Neil Diamond ran into Mick Jagger at the Los Angeles studios where they were both working on new albums. "He came by to see what the hubbub was about, and we kidded around," says Diamond, a tan, happy man who looks a decade younger than his sixty-four years but speaks in the slow Brooklynese of a real old-timer. "I told him, 'You business office made a big faux pas, because they booked yuh tour the same month I'm going out.' I don't think he liked that." Diamond titters. "I thought it was funny."

There's more truth to this than the Stones might like to admit: Diamond has told 120 million albums in his career, and his recent tour ranks with U2's and Kenny Chesney's as the top-grossing of this year. In November, he released 12 Songs, a Rick Rubin-produced album with the sound of his Sixties coffee-shop tunes: vocals, congas, a little keyboard and an acoustic guitar that he plays himself, for the first time in decades. The songs cast Diamond as a wise soul declaring "Love is all about we" and "Yeah, this crazy life around me, it confuses and confounds me/But it's all the life I've got until I die." (Hold "die" for three beats.)

By nature very shy, Diamond is semi-comfortable with his embrace as kitsch by hipsters and the high-concept cover band Super Diamond, and he was a little defensive when "this rap and rock & roll guy" rubin first called him. He was surprised to find a kindred spirit, even a fan. "Rick's got instincts and vision, and I got with that," he says. "He's a peaceful person, a kind of spiritual guru." Later he says, "I haven't seen him in a couple of days, and I mess him. I feel safe with him."

Safety is a priority for Diamond, who has worked with much the same staff in the same L.A. offices for thirty years. Tiny frog figurines, some of them strumming guitars, decorate available surfaces, and the bathroom walls are covered with needlepoint sayings (over the toilet, inexplicably: HOME IS WHERE THE HEART IS). Some of the staff ride in a motorcycle club called the Mild Ones, though Diamond recently put his bike away after a few falls. "We were mild but cool," he says.

|

Twice divorced, with two adult kids from each marriage, Diamond grew up the son of middle-class first-generation Jewish immigrants in Brooklyn's Coney Island, picking up the guitar at camp in the Catskills after he saw a kid playing one get swarmed by the ladies. He attended NYU on a fencing scholarship, but in 1962 he dropped out to become a fifty-dollar-a-week Brill Building songwriter, eventually writing the Number One hit "I'm a Believer." By then, Diamond was cutting his own songs for Bang Records: "Solitary Man," "Cherry, Cherry," "Girl, You'll Be a Woman Soon" and "Kentucky Woman."

Rubin pushed Diamond to listen to his earlier work for the first time in years, and in some cases decades. "He very politely asked me why my songs changed," says Diamond. "I was taking a page from the Beatles' book: Just let it fly, give it your best shot, make it interesting. Without realizing it, the records became bigger and bigger, and the songs became smaller and smaller." In the Seventies, he moved to Los Angeles, to a house in Laurel Canyon with mirrors on the ceiling. "I wouldn't have put them there, but there they were," he says. "It was the indoctrination into the L.A. way of life -- wow." It was also the beginning of the Diamond onstage persona: the sequin-jumpsuited Uncle Neil who looks deeply in your eyes while feeling your knee under the table.

Touring is something he loves, the late-night games of poker with the othe musicians and crew, all of them in the same hotel. Today, preparing to go on the road again, he's filled with excitement. He stops by a pet store ("Do you have bellls for cats?"), eats a hot dog ("I like to eat junk at home, so when I get on the road I can cool out") and heads to Fred Segal to shop for new socks.

"I'm happy with the way things have gone, in life," he says. "But worse than bad reviews is to be ignored. My dream is that this album will not pass without being noticed." ![]()

| The One You Need |

|

![]()

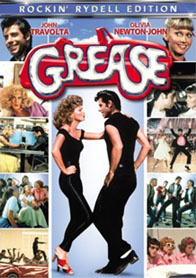

We're still hopelessly devoted to Sandy and Danny, summer lovin', and Greased lightning.

by Mandi Bierly in Entertainment Weekly

Grease

Rockin' Rydell Edition

John Travolta, Olivia Newton-John

PG, 11 mins., 1978

![]() t's a musical. About perky Australian transfer student Sandy falling for quintessential '50s American greaser Danny Zuko. That ends with the pair literally flying off in a car. And still we consider it a classic? Never underestimate the power of catchy tunes. Travolta's hips, and a sweet-yet-smutty script. But will this DVD, with its 12 new extras and limited-edition mini black (faux) leather T-bird jacked packaging, blow your bobby socks off? Well, that depends.

t's a musical. About perky Australian transfer student Sandy falling for quintessential '50s American greaser Danny Zuko. That ends with the pair literally flying off in a car. And still we consider it a classic? Never underestimate the power of catchy tunes. Travolta's hips, and a sweet-yet-smutty script. But will this DVD, with its 12 new extras and limited-edition mini black (faux) leather T-bird jacked packaging, blow your bobby socks off? Well, that depends.

If it's scores of anecdotes from Travolta and Newton-John you're after, no. Interviews from '78 just show how pretty they are, while a three-minute red-carpet chat from 2002, when the film was first released on DVD, only reveals they they're now veterans of the trite sound bite. (You're amazed at how comfortable you are seeing the cast again, John? How fascinating.) At least Travolta proves entertaining in footage from the 2002 DVD launch party, where he joins his costar on stage to sing "You're the One That I Want." It's required viewing for anyone who's ever karoake'd that song in public, or who intends to partake in this DVD's special sing-along feature. (You will see how ridiculous you looked.) The fact that Travolta later remembers the shoo-bop-bop bounce for "Summer Night," but has to check the TelePrompTer for the song's lyrics, is mildly disheartening, but it's perhaps the finest testament to choreographer Patricia Birch's unforgettable moves.

If it's scores of anecdotes from Travolta and Newton-John you're after, no. Interviews from '78 just show how pretty they are, while a three-minute red-carpet chat from 2002, when the film was first released on DVD, only reveals they they're now veterans of the trite sound bite. (You're amazed at how comfortable you are seeing the cast again, John? How fascinating.) At least Travolta proves entertaining in footage from the 2002 DVD launch party, where he joins his costar on stage to sing "You're the One That I Want." It's required viewing for anyone who's ever karoake'd that song in public, or who intends to partake in this DVD's special sing-along feature. (You will see how ridiculous you looked.) The fact that Travolta later remembers the shoo-bop-bop bounce for "Summer Night," but has to check the TelePrompTer for the song's lyrics, is mildly disheartening, but it's perhaps the finest testament to choreographer Patricia Birch's unforgettable moves.

Genuinely good times are found on the making-of doc (Stockard Channing says Jeff Conway insisted that Rizzo's "hickeys from Kenickie" be real) and throughout the recently recorded commentary by Birch and director Randal Kleiser, who note the many differences between Grease's Broadway and film scripts: In the stage version, for example, Kenickie sings "Greased Lightning" instead of Danny, which would have been a nice consolation prize for Conway (who'd played Zuko on Broadway but was demoted to the horny sidekick for the film) had the solo not been handed over to Travolta. Kleiser also drops all kinds of trivia. He points out an otherwise unremarkable scene Travolta asked to reshoot because the camera didn't catch his good side (the left, apparently); that some of the Coke signs in the Frosty Palace were blurred because producers had struck a product-placement deal with Pepsi; and that one of the movie's main dancers is Andy Tennant, who went on to direct Ever After and Sweet Home Alabama. That's the kind of minutiae we, the people who've already devoted about 143 hours of our lives to watching this movie, deserve. Maybe in the next edition -- which should also come in a Pink Ladies jacket, Paramount -- Travolta and Newton-John will play along. B+ ![]()

![]() Reader's Comments

Reader's Comments

No comments so far, be the first to comment.