![]()

| 1979: London Calls - America Answers |

|

![]()

Remaining members of the Clash talk about their groundbreaking, explosive,

still politically relevant album to mark its deluxe 25th-anniversary reissue.

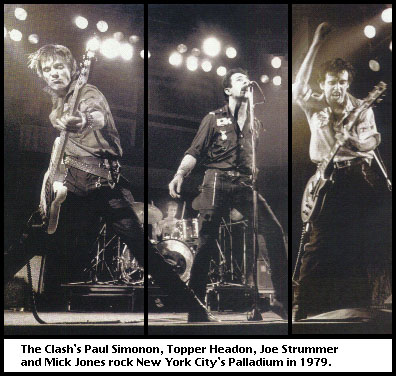

![]() he bass guitar went up, the bass guitar went down. In the two second interval before it splintered, photographer Pennie Smith captured the dramatic shot of Class bassist Paul Simonon smashing his instrument on stage at New York City's Palladium, Sept. 21, 1979. Smith recalls that mere moments before, she had been ready to pack up her camera gear. But when she saw Simonon looking "really, really fed up" and ready to blow a gasket, she decided to keep her camera at the ready. "I just got the one shot and that was it," she laughs. "End of roll of film."

he bass guitar went up, the bass guitar went down. In the two second interval before it splintered, photographer Pennie Smith captured the dramatic shot of Class bassist Paul Simonon smashing his instrument on stage at New York City's Palladium, Sept. 21, 1979. Smith recalls that mere moments before, she had been ready to pack up her camera gear. But when she saw Simonon looking "really, really fed up" and ready to blow a gasket, she decided to keep her camera at the ready. "I just got the one shot and that was it," she laughs. "End of roll of film."

That luck-induced, immortal image -- framed by pink and green lettering (echoing the cover of Elvis Presley's first LP, courtesy of designer Ray Lowry) -- would go on to grace the cover of the Clash's breakthrough album, London Calling, which they released just three months later. Although the band had mostly finished recording it shortly before embarking on a Yank-bashing, monthlong U.S. tour in the fall of '79 (in true punk style, they opened every set with "I'm So Bored With the U.S.A."), it didn't improve their moods: Paul Simonon chalks up his bout of bassicide to a general "frustration," and in retrospect, it's easy to guess why the angry young men of the Clash may have been feeling more cantankerous than usual.

"Airplay and sales for the Clash was pretty limited then," recalls Harvey Leeds, then head of Album Rock Promotion for the band's U.S. label, Epic Records. Indeed, by the end of the '70s, while poppier American punk and new-wave acts like Blondie and Talking Heads were scoring radio hits, the English punks, like the Damned and the Sex Pistols, had yet to make an impact. And for all their antiestablishment rhetoric, the Clash desperately wanted to "break out and break America and be kind of global," as late frontman Joe Strummer (who died in 2002 of heart failure) once said.

|

Needless to say, there was a lot riding on the Clash's third record. A quarter century down the line, history has shown that London Calling was the band's watershed, both a critical and commercial success that turned this quartet of scruffy yobbos into bona fide rock stars. From the apocalyptically chilling title track to the giddy closing choogle of "Train in Vain," the album was a wild, genre-jumping joyride. Whether denouncing drug addiction ("Hateful"), playing homage to ill-fated actor Montgomery Clift ("The Right Profile"), or delivering a pummeling antifascist broadside ("Clampdown"), the Clash was clearly a band at the top of its game.

Like Shakespeare, Citizen Kane, or the Beatles, the appeal of London Calling is timeless and peerless. To commemorate the 25th anniversary, Epic has released a deluxe, remastered edition of London Calling, complete with an additional CD of newly unearthed demos and a DVD directed by the band's longtime videographer and friend, Don Letts. Embracing the spirit of '79, we went to London to call on the surviving Clash members and some of their associates, to get the lowdown on their classic double LP.

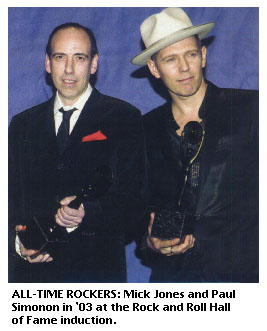

![]() triding into a room in London's legendary Groucho Club (named in honor of Groucho Marx's famous quip about not wanting to belong to any club that would have him as a member), Mick Jones and Paul Simonon look every inch the semiretired, slightly decadent gentlemen rockers. Slipping a Bloody Mary and puffing a Silk Cut, the lanky, now-balding Jones (who's been keeping busy producing Clash descendants the Libertines) is dressed in a loose-fitting dark suit. Simonon -- these days, a painter of some note -- is natty in a gangsterish fedora and sports clothes.

triding into a room in London's legendary Groucho Club (named in honor of Groucho Marx's famous quip about not wanting to belong to any club that would have him as a member), Mick Jones and Paul Simonon look every inch the semiretired, slightly decadent gentlemen rockers. Slipping a Bloody Mary and puffing a Silk Cut, the lanky, now-balding Jones (who's been keeping busy producing Clash descendants the Libertines) is dressed in a loose-fitting dark suit. Simonon -- these days, a painter of some note -- is natty in a gangsterish fedora and sports clothes.

Jones, whose ready grin is never far from the surface, lies down on one of the club's beds, praises its comfortableness, and tries to mentally click back to the spring of '79, when the band began hammering out London Calling's songs.

"Our backs were against the wall. We were thinking 'We better do something here,'" Jones admits. "I don't think we ever thought we were gonna go under or nothin', but on the other hand, we needed to consolidate what we were."

Part of that consolidation had to do with redefining what punk was -- especially since the first wave of British punk bands seemed to be rapidly falling by the wayside. "Even though we were great rivals, we were also great allies. Punk never really made it commercially. New wave sort of made it a little bit after. The first punks had a tough time. London Calling we chucked out the punk rule book. Punk was supposed to be about not having a rule book."

So it was goodbye to raging three-chord rama lama, hello to a fresh panoply of styles that included rockabilly ("Brand New Cadillac"), ska-reggae ("Revolution Rock"), R&B ("Wrong 'Em Boyo"), ballads ("Lost in the Supermarket") -- even touches of jazzbo cool ("Jimmy Jazz"). "It wasn't about just limiting ourselves to one sound," says Simonon. "It was all about, What about the sound over there, and the music over there? What if we mix that with this, and then put it like this?"

So it was goodbye to raging three-chord rama lama, hello to a fresh panoply of styles that included rockabilly ("Brand New Cadillac"), ska-reggae ("Revolution Rock"), R&B ("Wrong 'Em Boyo"), ballads ("Lost in the Supermarket") -- even touches of jazzbo cool ("Jimmy Jazz"). "It wasn't about just limiting ourselves to one sound," says Simonon. "It was all about, What about the sound over there, and the music over there? What if we mix that with this, and then put it like this?"

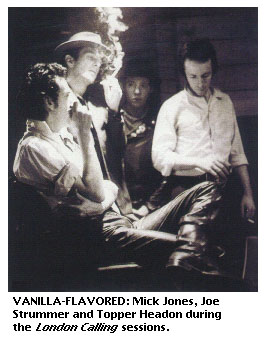

The Clash's new anything-goes aesthetic blossomed at Vanilla Studios, a down-at-the-heels rehearsal room in Pimlico, where the band began writing and demoing songs in the spring of '79. "We were totally oblivious to any outside influences," says Jones. "People from the label came by, and we usually took them out for a game of football, played them a couple of numbers. But we were a bit beyond them."

The songs came together quickly, with Jones composing and arranging the bulk of the music and Strummer supplying lyrics. Early, incomplete versions of many tunes can be heard on the so-called Vanilla Tapes, the collection of demos now found on the deluxe London Calling.

"We were most close at that time, and that helped us," says Jones. Though Strummer, the band's de facto leader, would dismiss Topper Headon in 1982 (blaming the drummer's heroin problem) and fire Jones the following year due to growing artistic differences, Jones says a the time their songwriting partnership seemed charmed. He cites the lovely "Lost in the Supermarket" as an example of just how empathetic his relationship with Strummer was: "He said he was trying to imagine what it must've been like for me as a kid."

When it came time to record the album proper, Guy Stevens, who had been the producer of Mott the Hoople -- one of Jones' favorite bands -- was asked to produce. Stevens' methods were unconventional: He'd once allegedly burned down a studio while recording a Mott album, and his problems with alcohol and drugs (he would OD in 1981) had gotten him all but blacklisted in the industry. The Last Testament: The Making of London Calling, the DVD now accompanying the album, shows footage of Stevens recklessly swinging a ladder and upturning chairs as the band plays -- simply to amp up the rock & roll atmosphere. "Guy had such spirit," remembers Headon, reached by phone. "When we recorded 'Brand New Cadillac,' we did it in one take. Guy went, 'Great take.' And I said, "No, no, it's too fast, it speeds up.' And he just said, 'All great rock & roll speeds up.'"

The entire album was laid down in a matter of weeks. Ironically, the last song the Clash recorded during the sessions, Jones' "Train in Vain," was never intended for inclusion. "We were going to give 'Train' [as a freebie] in the NME [New Musical Express, the British rock weekly]," says Jones. "And then for some reason they couldn't put it out. And since it was the last thing we recorded and the artwork had already gone to press, it was too late to list it on the album," They stuck it on anyway as an unlisted bonus track, and "Train" went on to become the Clash's first American hit single.

While London Calling certainly sped up the Clash's career trajectory, it also brought them that much closer to their end. Both Jones and Simonon agree that the split may have been inevitable, since the Clash gestalt had always been as combustible as their fiercest music sounded.

While London Calling certainly sped up the Clash's career trajectory, it also brought them that much closer to their end. Both Jones and Simonon agree that the split may have been inevitable, since the Clash gestalt had always been as combustible as their fiercest music sounded.

"You have to understand," says Simonon, "from day one, there was always a little rowing, and a bit of verbal [sparring]. So I was surprised it lasted as long as it did."

"Plus we never had any holidays, any time off," says Jones. "You know, it was like a family, it felt like a family. We were that close."

Not to speak ill of the dead, but are there still any bad feelings toward Strummer for booting Jones? (After firing Headon and Jones, Strummer put together a new edition of the Clash and released the abysmal Cut the Crap in 1985; in footage filmed circa 2000 for Westway to the World, a guilty Strummer admits he was in the wrong.)

Jones: "We made up..."

Simonon: "We've discussed all that and it's perfectly clear..."

Jones: "...pretty soon after..."

Simonon: "...that Mick was wrong."

Jones and Simonon crack up. "I was wrong all along," says Jones, sarcastically.

![]() he Clash would get bigger: 1982's Combat Rock went platinum before London Calling even sold its first million, and paved the way for stadium dates opening for the Who and TV appearances on Saturday Night Live -- but they would never be better. London Calling remains their masterpiece and, 25 years on, an album that fans and musicians continue to look to for inspiration, kicks, and spiritual sustenance. Bill Price, the album's engineer, chalks it up to the singular clarity of the band's artistic vision and the indelible nature of the songs.

he Clash would get bigger: 1982's Combat Rock went platinum before London Calling even sold its first million, and paved the way for stadium dates opening for the Who and TV appearances on Saturday Night Live -- but they would never be better. London Calling remains their masterpiece and, 25 years on, an album that fans and musicians continue to look to for inspiration, kicks, and spiritual sustenance. Bill Price, the album's engineer, chalks it up to the singular clarity of the band's artistic vision and the indelible nature of the songs.

"Joe Strummer made a very big point of wanting every song to have a particular identity," he recalls. "He'd say, 'This one's called 'London Calling.' I want it to sound like it's coming through fog over the river Thames.' He'd have a little anecdote for every song."

Letts gives credit to the formidable songwriting talents of the Strummer/Jones team: "To see those two guys work, it was such a beautiful thing. Jagger/Richards. Lennon/McCartney. Morrissey/Marr. Strummer/Jones. It doesn't happen that often."

I think that's the album when we all just jelled and it was like a piece of time that's been captured," says Headon.

When questioned about London Calling's enduring legacy, Jones looks off into space, considering. "I think," he offers, with suitable gravitas, "that was the album where we became men." ![]()

| Killer Kinks |

|

![]()

The underdogs of the British Invasion get some much-needed reissues.

by Richard Skanse in Rolling Stone

![]() t's not always easy being a Kinks fan in a Beatles 'n' Stones world -- singer-songwriter Ray Davies and his guitarist brother, Dave, were responsible for some of the greatest rock of the British Invasion, but they've always been in and out of fashion in the States, just as many of their finest albums have been in and out of print. Boom times may have finally arrived for dedicated followers of these perennial underdogs, however. To mark the Kinks' fortieth anniversary, fifteen of their post-Sixties albums are being updated to audiophile-quality hybric-SACD, and 1968's The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society has resurfaced as a sprawling three-disc import.

t's not always easy being a Kinks fan in a Beatles 'n' Stones world -- singer-songwriter Ray Davies and his guitarist brother, Dave, were responsible for some of the greatest rock of the British Invasion, but they've always been in and out of fashion in the States, just as many of their finest albums have been in and out of print. Boom times may have finally arrived for dedicated followers of these perennial underdogs, however. To mark the Kinks' fortieth anniversary, fifteen of their post-Sixties albums are being updated to audiophile-quality hybric-SACD, and 1968's The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society has resurfaced as a sprawling three-disc import.

Pete Townshend has hailed Village Green as Ray Davies' very own Sgt. Pepper. That almost doesn't do Village Green justice: Davies' nostalgic paean to the simple life in a quaint English village was an anomaly even in the pastoral-minded Sixties; certainly nobody else around the Summer of Love was espousing the virtues of china cups and virginity. Underneath its genteel English whimsy lurk some of Davies' most gorgeous songs (the title track), as well as his most astute observations and character studies ("Big Sky," "Do You Remember Walter"). The deluxe edition offers the album in both stereo and mono mixes, along with thirty-two bonus tracks, including gems such as the terrific non-album singles "Days" and "Wonderboy," and the funny midlife lament "Where Did My Spring Go."

Pete Townshend has hailed Village Green as Ray Davies' very own Sgt. Pepper. That almost doesn't do Village Green justice: Davies' nostalgic paean to the simple life in a quaint English village was an anomaly even in the pastoral-minded Sixties; certainly nobody else around the Summer of Love was espousing the virtues of china cups and virginity. Underneath its genteel English whimsy lurk some of Davies' most gorgeous songs (the title track), as well as his most astute observations and character studies ("Big Sky," "Do You Remember Walter"). The deluxe edition offers the album in both stereo and mono mixes, along with thirty-two bonus tracks, including gems such as the terrific non-album singles "Days" and "Wonderboy," and the funny midlife lament "Where Did My Spring Go."

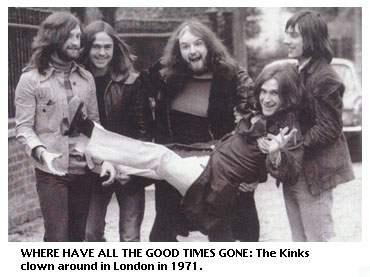

If Village Green is the Kinks' Sgt. Pepper, the wonderfully ramshackle Muswell Hillbillies (1971) is their Exile on Main Street. the opening "20th Century Man" rocks like classic Sixties Kinks, but the rest -- a bittersweet examination of working-class London suburbia scored to English dancehall ("Alcohol") and boozy ragtime and country & western ("Acute Schizophrenia Paranoia Blues," "Muswell Hillbilly") -- set the anything-goes tone for what would be the Kinks' most adventurous decade. Ray Davies went on to lead the band down a rabbit hole of increasingly wonky musical-theater experiments, concluding with 1975's Schoolboys in Disgrace. Schoolboys is the best of the bunch, as Dave Davies reasserts his presence like a hyperactive kid set free. Ray himself returned to form with 1978's Misfits, a collection of exquisitely drawn observations that harken back to 1967's landmark Something Else.

If Village Green is the Kinks' Sgt. Pepper, the wonderfully ramshackle Muswell Hillbillies (1971) is their Exile on Main Street. the opening "20th Century Man" rocks like classic Sixties Kinks, but the rest -- a bittersweet examination of working-class London suburbia scored to English dancehall ("Alcohol") and boozy ragtime and country & western ("Acute Schizophrenia Paranoia Blues," "Muswell Hillbilly") -- set the anything-goes tone for what would be the Kinks' most adventurous decade. Ray Davies went on to lead the band down a rabbit hole of increasingly wonky musical-theater experiments, concluding with 1975's Schoolboys in Disgrace. Schoolboys is the best of the bunch, as Dave Davies reasserts his presence like a hyperactive kid set free. Ray himself returned to form with 1978's Misfits, a collection of exquisitely drawn observations that harken back to 1967's landmark Something Else.

Misfits themselves, the Kinks were as surprised as anyone by their unlikely turn as bona fide arena rockers in the Eighties. Fittingly, 1980's One for the Road is more punk than dinosaur, though latter-day fare such as the pulsing "(Wish I Could Fly Like) Superman" works better than the hot-rodded update of "You Really Got Me." 1981's Give the People What They Want is twice as punchy, from the ironic fist-pumping of the title track to the clever self-plagiarism of "Destroyer." Even smartly balanced by the devastatingly sad "Art Lover" and the domestic ennui of "Yo-Yo," this is the sound of the Kinks "rocking out and having fun," to quote the sparkling "Better Things" -- and finally getting their just deserts.

Misfits themselves, the Kinks were as surprised as anyone by their unlikely turn as bona fide arena rockers in the Eighties. Fittingly, 1980's One for the Road is more punk than dinosaur, though latter-day fare such as the pulsing "(Wish I Could Fly Like) Superman" works better than the hot-rodded update of "You Really Got Me." 1981's Give the People What They Want is twice as punchy, from the ironic fist-pumping of the title track to the clever self-plagiarism of "Destroyer." Even smartly balanced by the devastatingly sad "Art Lover" and the domestic ennui of "Yo-Yo," this is the sound of the Kinks "rocking out and having fun," to quote the sparkling "Better Things" -- and finally getting their just deserts. ![]() The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society * * * * *, Muswell Hillbillies * * * *, Misfits * * * 1/2, The Kinks Present Schoolboys in Disgrace * * *, One for the Road * * *, Give the People What They Want * * * *

The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society * * * * *, Muswell Hillbillies * * * *, Misfits * * * 1/2, The Kinks Present Schoolboys in Disgrace * * *, One for the Road * * *, Give the People What They Want * * * *

![]() Reader's Comments

Reader's Comments

No comments so far, be the first to comment.